1

Many significant films were inspired by works of art or even entire artistic eras. In the 1920s and 30s, stylistic trends in visual art and film had, to some extent, a mutual effect on each other. For example, the surrealist Salvador Dalí worked in conjunction with film director Luis Buñuel on An Andalusian Dog. Another example is the bizarrely distorted stage design in Robert Wienes’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, which was influenced by the expressionist cityscapes of Ludwig Meidner and Lyonel Feininger. In Battleship Potemkin, Sergei Eisenstein focused on the ideas of Cubism and Constructivism and attempted to overcome the static limitations of images through the dynamism of the montage.

In 1936, Jean-Renoir released the film, A Day in the Country, which resembled the impressionist pictures of his father, Pierre Auguste Renoir, through his choice of motifs, the sensual presence of the actors, and the sophisticated camera work. Ten years later, Robert Siodmak transposed Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks into a film set in the opening sequence of the film noir, The Killers. Hopper’s pictures also influenced directors, such as Alfred Hitchcock (Rear Window, Psycho, Marnie) and Wim Wenders (Paris, Texas).

The examples of films presented here will formally illustrate the relationships between painting and film and show how the painting styles of the corresponding pictures were directly transposed into cinematic sequences. This will be done by an algorithm developed by Leon A. Gatys, Alexander S. Ecker and Matthias Bethge, which will be described in detail in the Technical Aspects section.

2

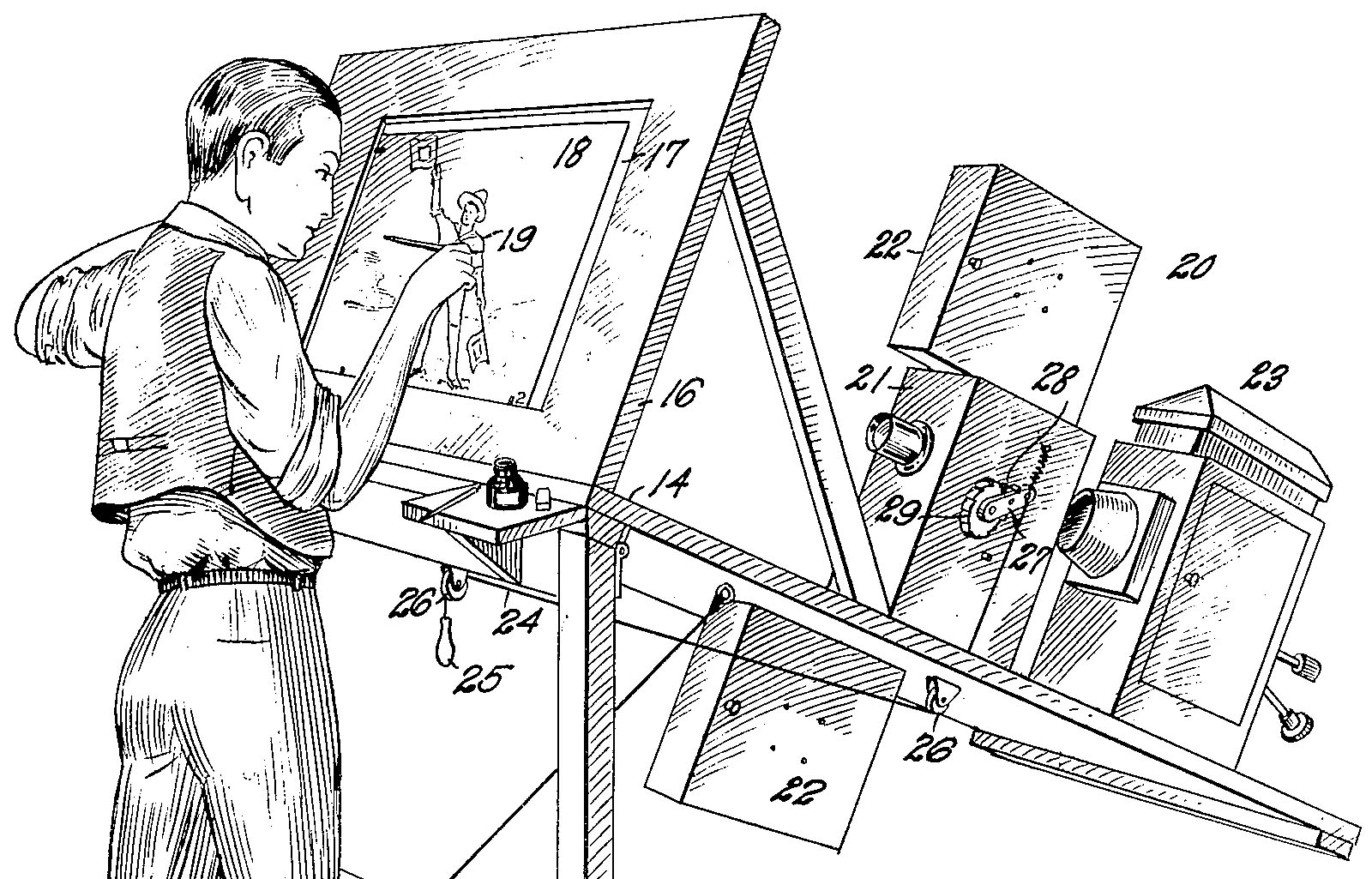

The act of painting over motion picture footage is a relatively old technique and was first used in 1914 in the animation series, Out of the Inkwell. The film producer, Max Fleischer patented his rotoscope device in 1917, which was used to project film images onto a matt glass pane via rear projection to enable the images to be traced, frame-by-frame.

As the decades passed, the rotoscoping technique was put to use in films, such as Hitchcock’s The Birds and the early Stars Wars films. Since the 1990s, the task of rotoscoping film sequences has been performed on computers. It was primarily the introduction of After Effects, which opened up a range of new creative possibilities in film title design. Rotoscoping is often used in post-production for retouching – removing power cables and other undesired aspects from the film. The technique is similar to the removal of dust and scratches in film restoration.

A general distinction is made between the hand-drawn, bitmap-based technique and a semi-automated, vector-based technique. The classic drawing technique is used by Ralph Bakshi’s Lord of the Rings from 1977. Other approaches were taken by Richard Linklater in Waking Life (2001) and A Scanner Darkly (2006) and both films were rotoscoped using Bob Sabiston’s vector-based program, Rotoshop.

Still frames from Loving Vincent and Robin Hood

Still frames from Loving Vincent and Robin Hood

In 2017, the first fully painted feature film is set to be released by film directors Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman, entitled Loving Vincent. The film chronicles the life and work of Vincent van Gogh and combines traditional oil painting with digital animation techniques. Every single film frame will be painted by hand. Many other artists in the field of motion picture design are also increasingly using analogue techniques: for the opening title sequence of Robin Hood (2010), Gianluigi Toccafondo printed film images onto paper, painted over them and then scanned them back in digitally. Gareth Smith and Jenny Lee used a similar technique in 2007 for the opening title sequence of Juno.

3

When using the rotoscoping technique, questions are always raised as to its applications and the artistic impressions that can be created. Justifying its use for technical aspects (retouching, visual effects, painted effects, compositing) is fairly simple, but when it comes to more creative painting techniques, the question is often asked: Why should an existing motion picture be painted over at all? For rotoscoping pioneer, Max Fleischer, the answer was very clear. With the help of imagination alone, an animator could not reproduce realistic movements and the results were mechanical and unnatural (see Seymour 2011). For instance, the dance scenes in Disney’s Snow White were rotoscoped from film recordings of a dancer.

But why would a motion picture film like A Scanner Darkly be rotoscoped? Director Linklater emphasises that the technique enhances not only the viewer’s experience of the film, but also becomes part of the storytelling process. Elements such as paranoia, conspiracy and despair can be intensified using rotoscoped animation (see Materna 2006).

Still frames from A Scanner Darkly and Juno

Still frames from A Scanner Darkly and Juno

Gareth Smith similarly justifies the use of hand-drawn techniques in the opening sequence of Juno: “It seemed natural to show the credits while the audience followed Juno from the opening scene, through her neighborhood, and to the convenience store where she gets her pregnancy test. This decision allowed us to do something a little unusual for an opening title sequence: focus the sequence entirely on the main character of the film. This allowed the audience to really get a sense of, and get immersed in, Juno’s unique, quirky point of view of the world.” (Vlaanderen 2008)

4

Rotoscope techniques are used in a variety of fields aside from film production, post-production and film title design, such as advertisements and music video production, for example. Fully-automated style transfer using the neural-style-algorithm appears to be suitable for short film sequences, such as an animated title sequence or advertising spot. In contrast to the examples shown here, however, the results must be in full resolution and feature top image quality. With a correspondingly powerful GPU, it would even be possible to produce longer clips, such as music videos.

URL: http://www.awn.com/animationworld/scanner-darkly-animated-illusion (accessed February 2017)

Seymour, Mike: The Art of Roto. 2011.

URL: https://www.fxguide.com/featured/the-art-of-roto-2011/ (accessed February 2017)

Vlaanderen, Remco: Juno. Forget the Films, Watch the Titles. 2008.

URL: http://www.watchthetitles.com/articles/0069-Juno (accessed February 2017)

Zinman, Gregory: Between canvas and celluloid: Painted films and filmed paintings. In:

The Moving Image Review & Art Journal (MIRAJ), Volume 3, Number 2, 1 December 2014, 162-176.